HKW Berlin

19 Hours at the Kiosk

2012

Berlin, DE

Commissioned by Valerie Smith, Haus der Kulturen der Welt.

Curated by Valerie Smith.

Contributors to Architecture and Ideology include Amateur Architecture Studio (Wang Shu & Lu Wenyu), Arno Brandlhuber, Ângela Ferreira, Terence Gower Initiative, Weltkulturerbe Doppeltes Berlin, Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle, Studio Miessen, Marko Sančanin (Platforma 9, 81), Eran Schaerf, and Supersudaca

Download:- Spatial Design by Studio Miessen

- Project Leader: Markus Miessen, Diogo Passarinho, Yulia Startsev, Martin Pohl

- Team: Mahan Shirazi, Hamed Bukhamseen, Caspar Noyons

- Book selection curated by: Archive Kabinett (Chiara Figone, Clara Miranda Scherffig)

- Project developed for the rooftop kiosk at Haus der Kulturen der Welt.

- Contributions to 19 hours at the kiosk: Federica Bueti, Lars Eidinger, Simon Fujiwara, Das Gift (Barry Burns, Rachel Burns Phil Collins, Sinisa Mitrovic), La Stampa (Jan Verwoert, Jörg Heiser, Thomas Hug, Günter Reznicek, Jons Vukorep), Johanna Meyer Grohbrügge, Patricia Reed, Rimini Protokoll (Daniel Wetzel), Ashkan Sepahvand, Something Fantastic (Julian Schubert, Elena Schütz), Felix Vogel, Joanna Warsza, Wet Nails, Joao Salaviza, Hito Steyerl, Maren Ade, and Eduardo Coutinho.

- Production Team: Pia Thilmann, Daniela Wolf, Kerstin Feldmayer, Johana Zinecker

- Photographers: Thomas Eugster and Judith Affolter

- Catalogue published by: Hatje Cantz Verlag

Between Walls and Windows. Architecture and Ideology

The former congress hall was an architectural icon and a paradigm of post-war modernity which manifested itself as part of the International Construction Exhibition in Germany. It was commissioned by the US government in 1956 and designed by Hugh Stubbins, erstwhile assistant of Walter Gropius in America. For ideological reasons, the building was constructed on an artificial hillock as a symbol of freedom that could be seen from afar in both East and West.

During September 2012, as part of the exhibition Between Walls and Windows: Architecture and Ideology, curated by Valerie Smith, this architectural landmark could be experienced anew as a large-scale sculpture, reinterpreted through artistic and architectural interventions that lay bare the ideological agenda of post-war modernity.

The architecture of the former congress hall and the history behind it form the focal point of Between Walls and Windows. Architecture and Ideology. The artistic approach focused not on the building itself but on the ideas and questions which architecture answers, as an instrument of construction history, philosophy and politics.

The project presented ten location-specific new productions by international artists and architects, who transformed the interior spaces and exterior surfaces of Haus der Kulturen der Welt, facilitating a discussion of all the things “architecture“ can be. The exhibition placed the local history of the former congress hall in a new, contemporary and global context and cast a spotlight on the Haus der Kulturen der Welt as a sculpture.

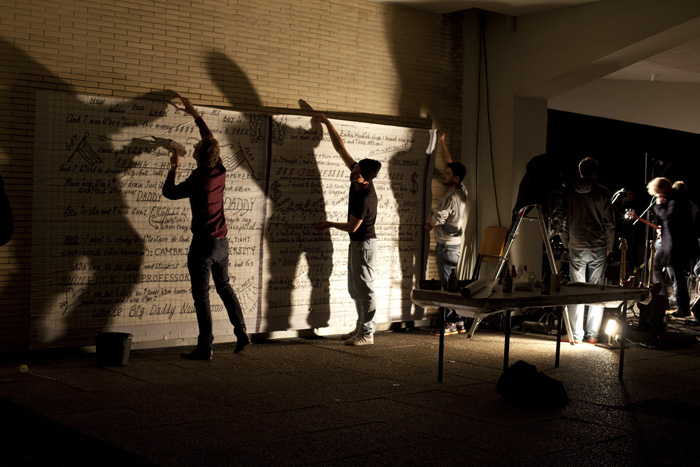

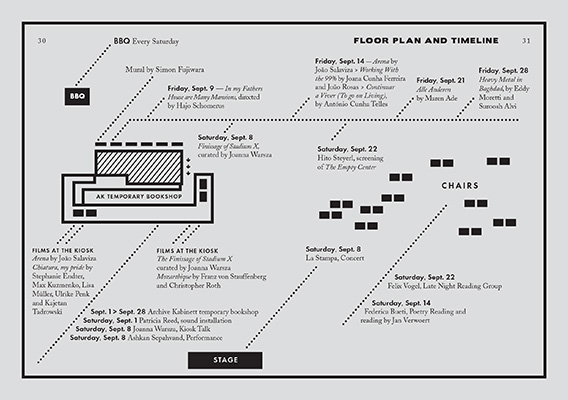

Studio Miessen: 19 hours at the kiosk

This temporal intervention presented a spatial and programmatic scenario through the reinterpretation of one of the original 1950s architectural elements of the Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW). The project created an informal space of assembly around and developed through the architecture of the existing rooftop kiosk, referring to the ideological attempt of the former Congress Hall to be both a highly visible and ideologically charged symbol of freedom, facing—in its original conception—the Reichstag and, later, the Bundeskanzleramt.

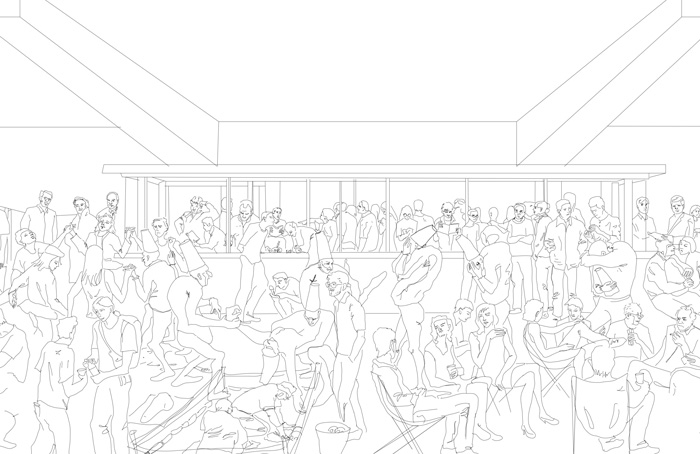

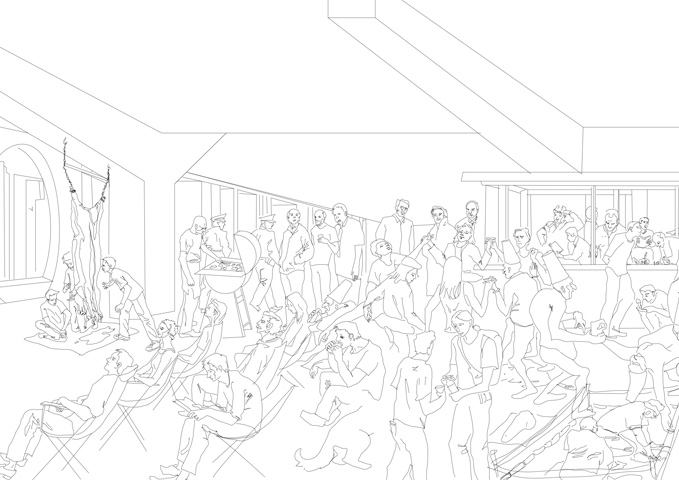

19 hours at the kiosk was based on an ephemeral master plan that refers to two strains of thought initiated by Mikhail Bakhtin and Cedric Price; that of the carnivalesque-dialogic, and of non-prescriptive architecture. A series of external authors were involved in different sets of curatorial actions, including reinterpretations of the content on display, readings, a concert, food preparation, rehearsals, screenings, alcoholic consumables and temporary spatial and archival installations, while a set of informal (architectural) elements created a direct confrontation with the audience, participants and, in the line of sight, the federal institutions. Cruiseliner deck chairs—used in the tradition of English architect Cedric Price’s seminal lectures at the Architectural Association in London—allowed for a night-time perspective of the state-political landscape east of the HKW and the former death-zone surrounding the Berlin Wall. Many of Cedric Price’s projects—such as the Fun Palace or the Brunswick—have distinct features that resemble Bakhtin’s observations of the carnivalesque: an incomplete structure, the capacity to change according to the situation, and the structure’s dependence on what is happening inside it. Price argued against the production of permanent, specific spaces for particular functions, and instead advocated analysis of the motivations that might give rise to such structures. In his concept for the Fun Palace one could “choose what you want to do – or watch someone else doing it. Learn how to handle tools, paint, babies, machinery, or just listen to your favourite tune. Dance, talk or be lifted up to where you can see how other people make things work. Sit out over space with a drink and tune in to what’s happening elsewhere in the city. Try starting a riot or beginning a painting – or just lie back and stare at the sky.”

The existing kiosk was transformed into a vitrine, archive, and reading room, utilizing a series of newly designed and constructed displays and surfaces, in order for the kiosk to assume the role of a walk-in bookshelf. This element explored the theme of Architektur und Ideologie through the display of published and unpublished material. Bakhtin argued that no aspect of language exists in a vacuum, books refer, quote, and argue with one another. This reflected the complexity of ideology in relation to time as any given text is in constant negotiation with other texts, conveying not only its own meaning but also mediating between the meaning of the preceding written work and anticipating the meaning of future work, engaged in an endless re-description of the world. Here, printed matter was understood as an architectural element that interacted with architecture as though it were a text.

With regard to access to content and visibility of the interior condition, the inside and the outside of the kiosk collided. The kiosk was re-appropriated as a temporary enabler rather than an official architectural symbol to be used in a prescribed way: to the viewer and visitor, the space presented, at times, a harshly hermetic setting that acted, simultaneously, as an informal social gathering space only when activated for 19 hours during the month of September. The kiosk adopted the framework of the carnival, where “official” and “unofficial” worlds depended on time, requiring that both states existed in the same object and that one state is the “norm”. When there were no events and the kiosk was closed it became a hermetic vitrine.

Exploring the difficulty of framing ideology in time, the project interrogated the importance of the ephemeral as an ideological relic, based on ritualized actions in space as a procession. In this regard, the audience was understood as a non-aligned multitude of active agents who – simply by their presence – provided a prop and backdrop to activate the space and give it meaning. Meanwhile, a series of chosen, passive agents were documenting the different events, possibly creating conflicts between different social groups.

During carnival, for example, as the social hierarchies dissolved individuals addressed each other in a mocking manner and made use of abusive words in an affectionate manner. This social framework suspended the normative social protocol, developed into a direct approach, in which members of different communities could speak plainly to one another. The alternate dimension of Carnival has historically been explored by many authors and thinkers as a pressure valve for conflicting forces in society. The uniqueness of Bakhtin’s thought was that within carnival he found that these shifts were not temporary but went beyond carnival to affect the structure of a society as a whole, in the same way that texts affect each other. The carnivalesque created a condition through which the official and informal worlds were combined: an autonomous zone that temporarily united bodies. As a temporal carnivalesque framework–by default–it required that things “return to normal,” however, that “normal” was informed by what preceded it. It might be argued that ideology was at its strongest when it appeared to be absent or naturally present, and it might have been from this position that a critical position might have taken form.

A catalog with numerous texts and a comprehensive photo section was being published by the Hatje Cantz Verlag to mark the exhibition’s opening on the 1st of September, 2012.