SKOR AAA 1

Actors, Agents and Attendants: Speculations on the Cultural Organization of Civility

2010

Amsterdam, NL

Commissioned by SKOR, Foundation Art and Public Space

With contributions from Fulya Erdemci, Andrea Phillips, Mark Fisher, Steven de Waal, Alfredo Jaar, Edi Rama, Anton Vidokle, Chto delat/ What is to be done?, Gavin Wade, Ann Demeester, Margreet Fogteloo, Theo Tegelaer, Beatriz Colomina, Hedy d’Acona, Matthijs Bouw, Arjen Oosterman, AA Bronson, Ultra-red, Bik Van der Pol, Nils van Beek, Mari Linnman, Sally Tallant, Mika Hannula, Willem Geerlings

- Concept and format: Fulya Erdemci, Andrea Phillips and Markus Miessen

- SKOR editorial team: Nils van Beek, Mariska van den Berg, Christina Li, Theo Tegelaers

- Curator expert meetings: Mariska van den Berg

- Curator Artist Positions and film programme: Christina Li

- Project coordinator and co-curator of Artist Positions: Fleur van Muiswinkel

- Project assistants: Hanneke Janssens, Simone Kleinhout

- Curatorial assistant film programme and symposium : Benoit Loiseau

- Communication and PR: Nienke van Beers

- Logistics: Merel Driessen

- Photography by: Gert Jan van Rooij, Job Janssen, Stefanie Grätz

- Spatial Design: nOffice (Miessen Pflugfelder Nilsson)

The symposium Actors, Agents and Attendants connected contemporary debates about care and citizenship in contemporary art, philosophy and politics to realities of healthcare organisation in The Netherlands and internationally. It highlighted the work of artists and curators, who are working across these fields while questioning the role of contemporary art in its ameliorative function.

The first day of the symposium focussed on care as an artistic, philosophical and political concept. The second day focussed on the specific politics of healthcare provision and artistic and curatorial responses to this – bringing together two areas of practice that are often divided but in fact share many concerns. The event attracted a crossover-audience and made the debates accessible across these audiences through clear descriptions and directions.

Symposium summary report by Rory Hyde:

1.1 Introduction by Fulya Erdemci & Andrea Phillips

“The Netherlands sits at the mid-point between the welfare state and neoliberalism.” With this statement, Fulya Erdemci, director of SKOR, opened the symposium by establishing the broader socio-political challenges facing cultural organisations, artists and the healthcare sector today. The recent coming to power of centre-right coalition governments in Holland and the UK in particular, and the threats to public sector funding that they bring, would be a recurring concern throughout the 2 days. But instead of resignation, Erdemci instead encouraged the seeking of new opportunities and roles for cultural agents in this altered context. In particular, SKOR aims to reclaim its role internationally as responsible to society, by providing new vision and exploring new modes of commissioning, particularly in regard to healthcare. Andrea Phillips, director of Research Programmes at Goldsmiths University London and day one chair, expanded on this notion of healthcare to include “the cultural organisation of civility.” ‘Care’ is understood as a common concern, one that extends from literal healthcare institutions, to the concepts of social care assumed within curatorial practice, and the ways in which artists (in particular Thomas Hirschhorn’s ‘Spinoza Monument’ in Amsterdam’s Bijlmeer, and Elmgreen & Dragset’s ‘Welfare Show’) are challenging strategies of public participation or interrogating political ideology through their work. But Phillips also cautions the use of such simplistic distinctions between ‘artist’, ‘public’ and ‘client’. Is there even such a thing as a describable ‘public’? And can we assume that it is one, which needs ‘care’? Under this model, artists become carers and the public become patients. Phillips concludes by encouraging the imagining of “new forms beyond this status quo”, enabling a shift from “care for the community to a commons of care.”

1.2 Mark Fisher

If the title of British Philosopher Mark Fisher’s presentation We’re Not All in This Together: Public Space and Antagonism in the Wake of Capitalist Realism was not direct enough, he offered us a more concise, but no less bleak, alternative: Fear and Misery in Neoliberal Britain. And miserable it is. Fisher opened with a dystopian description of a staff member attempting to navigate the relentless bureaucracy and dysfunctional systems of a typical British educational institution. The swipe card doesn’t work, the phone is ringing, the room is locked, the evening streets are filled with violence and vomit, and the drugs don’t help because there’s nothing wrong with you. It quickly becomes clear that Mark himself is the victim of these infringements of civility, infringements that will only get worse as the funding cuts take their toll. If this emphasis on the UK context were to be seen as out of place at a symposium held in Amsterdam, Fisher sardonically justifies it as a “perhaps what * Europe has to look forward to.” As the Dutch welfare state is increasingly eroded, there exists no alternative to what Fisher describes as ‘capitalist realism’ - the all-encompassing ideology of neoliberalism and post-fordism. To quote Slavoj Žižek, “it is easier to imagine the end of the world rather than the end of capitalism.” How this plays out culturally and in relation to care is particularly foreboding. The Cameron-Clegg government describe a ‘Big Society’; a combination of the ultimate faith in market forces to provide better services than the state, and the rise of what Fisher dismisses as ‘magical volunteerism’. When public funding is cut, somehow community volunteers will step in to fill the void at no extra cost, which with high private debt and unemployment, is — like the end of capitalism — difficult to imagine. Fisher’s prescription for an alternative is characteristically anarchist: the new public sphere will have to be built by coordinated refusal. Antagonism is a source of power. What might happen if we awaken from our complicit acceptance of the status quo and refuse to comply with our assigned roles in society?

1.3 Steven de Waal

Founder and Chairman of Public SPACE Foundation, and currently campaigning for the leadership of the Dutch Labour Party (PvdA), Steven de Wall offered a practical perspective in contrast to Mark Fisher’s preceding academic presentation. Indeed, the contrast between the two speakers could not be more striking, as de Waal seemed to advocate the precise model that Fisher had warned of moments earlier. Described as a ‘cooporatist system’, de Waal’s work seeks to expand the role that private companies and private individuals can play in offering social care. This model is not without precedent in the Dutch context, where the original public service organisations of the 19th century — such as public housing, nursing homes and universities — were first set up by the citizens, a model which the state then copied after WWII. Many of these private non-profits continue to coordinate the public domain today, but the new strategy is to make them increasingly commercial. The reason for this stems from the economic burden on government to reduce spending, but also from a more ideological perception that in Holland “we are possibly at the end of the expectation that government and politicians are responsible for all things.” People want to take responsibility for themselves. A statement from the audience put a human face on what this might mean in practice; “It’s very troubling to go into a Dutch nursing home and to not know whether your mother has been washed this week or last week * the state is not doing a good enough job, when there could be an informal system put together with women from the neighbourhood.” To enable family members and members of the community to assist in these kinds of scenarios could not only lessen the cost on government, but could also lead to greater social cohesion. As de Waal concluded, “we need to explore these various options for informal care — not because of finance — but because it’s what people want.”

1.4 Alfredo Jaar

Chilean artist, architect and filmmaker, Alfredo Jaar, presented a number of public projects from spanning three decades. A museum in Skoghalls, Sweden, was intentionally burned after only 24 hours; 1 million passports in Helsinki in a comment on Finland’s immigration policy; a musical dialogue bridging the US-Mexico border in memory of those who had died attempting to cross; a conversation space centred around a chandelier in a derelict church in Leipzig; a light installation that gave an ambient presence to the homeless of Moreau, Canada; and a lighting installation in memory of the victims of the Pinochet regime in Santiago. What connected each of these projects is an exploration of alternate possibilities for public space. As Jaar stated, “Public space is disappearing quickly, it is under threat from corporations and governments. We need to try and create little cracks, to convert these spaces of consumption into spaces of resistance; spaces of hope.” Developing out of a process of research and public consultation spanning years, Jaar’s interventions are not imposed from above, but firmly grounded in the concerns and ambitions of a place. The success of these projects is ultimately tied to the artists’ independence. Jaar firmly asserts his freedom from constraints of a client and a brief. His work is not instrumental in government’s regeneration or beautification programs, but operate autonomously as a means for creating new modes of awareness about a place or about an issue. Perhaps because of this independence from larger forces of development, Jaar admits “frustration at not achieving more,” and yet defends the scale of these interventions as “even though projects achieve very little, these matters need our attention.”

1.5 Edi Rama in conversation with Fulya Erdemci

“The city was like a train station with everybody trying to leave.” When artist Edi Rama became mayor of Tirana Albania in 2000, he inherited a city of anarchy and dysfunction, and a budget that did not meet his ambitions to repair it. Instead, he painted decrepit buildings in bright colours, deploying colour as a tool to effect social change and creating a new relationship between the municipality and the people. In a city ravaged by war and a political vacuum following the fall of socialism, Rama managed to shift the public consciousness to something more optimistic. “For the first time, the conversation in the country turned from how to get out, to colours.” To spend money when there is little available on what is seemingly an artistic exercise in beautification seems unjustifiable. Rama recounts an EU advisor’s shock, “please stop it, taxpayers will not tolerate it, and it is not European standard.” But Rama insists “it is not an artistic intervention, it is politics with no money.” The colours stood as a symbol of change, and instilled a sense of pride and ownership amongst the inhabitants. As Rama states, “people began to care about their place. We didn’t add more police, but people felt safer. And in the coloured streets, we had 100% tax collection.” Despite the overwhelming success of the painting program, Rama insists it is not a model that can be exported to other circumstances, but simply “a response to a city that was completely dysfunctional.” However he concedes it does stand as a source of inspiration, “that beauty can be effective in improving the rule of law instead of repression or control.” Rama also plans to expand the program by inviting international artists to paint particular buildings, transforming Tirana into an open air contemporary art museum, attracting investment and the tourist dollar to further energise Albania’s economy.

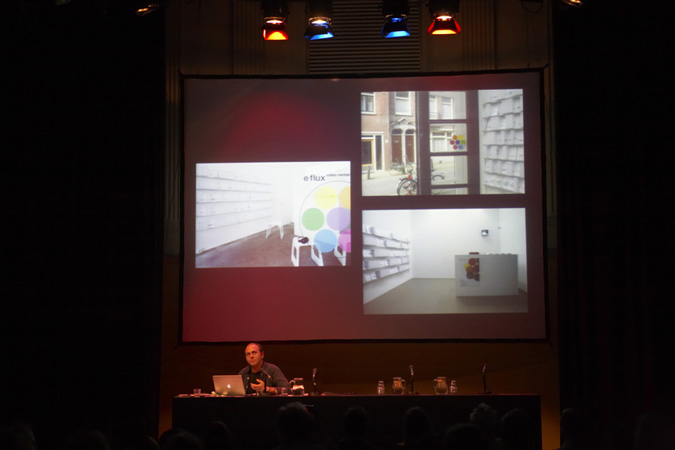

1.6 Anton Vidokle

Anton Vidokle, artist and founder of e-flux, presented his explorations beyond the exhibition format to engage the public. In a cultural context where the public has been replaced by a passively entertained audience, Vidokle’s projects seek to reclaim the transformative function of art, through new models of participation and new platforms for dissemination. We are given a brief spin through his key projects over the last decade, beginning with e-flux, the website and mailing list he co-founded in 1999 that has since spawned a journal, video lending library and established itself as a key broadcaster of art events and information with a global reach. While e-flux engaged the web as a legitimate platform outside existing means of production, other projects including the Image Bank for Everyday Revolutionary Life, the Martha Rosler Library, Pawnshop and United Nations Plaza each similarly challenge the space for and means for dissemination of cultural production and value. Vidokle’s latest project Time/Bank is a “platform where artists, curators, etc can engage time and skills * ideas and actions that seem to have no value can gain a sense of worth.” Via the website, participants can exchange their skills or services for ‘time credits’ which can be used in further exchange, or to purchase books in the New York Time Store. Vidokle explains his hope is “to create an immaterial economy, to help create a value for the many exchanges that already occur within the field of art.” Through the creation of this economic network, the aim is to also cultivate new social networks within the artistic community. Importantly, unlike the art world, which is “a demonic predatory space”, the art community already holds an incredible amount of trust. “Time / Bank is a means to expand this trust beyond local communities.”

1.7 Chto Delat / What is to be Done?

Dmitry Vilensky presented the work of the Russian artist collective Chto Delat that builds upon the early 20th century Soviet radical art and architecture that blurred the distinction between art and life. Drawing upon the concept of ‘crystallisation’, Chto Delat transform institutional spaces into platforms for political debate and public engagement. Like the previous presentation by Anton Vidokle, Vilensky also laments the passivity of contemporary art audiences, where “a visit to the museum could be compared to a visit to the opera; there is something very wrong with that.” In an attempt to short-circuit this complacency, Chto Delat look back to a point in Russian heritage where aesthetic and political agendas were indivisible. In particular, Alexander Rodchenko’s 1925 design of a Soviet Activist Club is a key source; which Chto Delat rebuilt from original photographs in Eindhoven’s Van Abbe Museum in 2009. As a space independent from state organization or from formal education systems, the Activist Club offers an alternative forum “where art can attain its emancipatory role in society.” Despite the end of socialist rule in Russia, the collective have not had a solo show in their home country since 2006, due to ambiguous state restrictions that Vilensky describes as “a form of soft-censorship.”

1.8 Panel discussion: Steven de Waal, Gavin Wade and Mark Fisher, moderated by Ann Demeester

After the conflict of opinion raised earlier in the day between Mark Fisher and Steven de Waal, many in the audience were looking forward to this opportunity for each to defend their positions. The session opened with Gavin Wade, director of Birmingham art space Eastside Projects, reciting a spoken word piece by the artist group FREEE. By endorsing the lines “fuck globalisation * we are not the tailors of utopia * nor the humanitarian curators”, Wade’s views would seem to align with Fisher’s extreme opposition to the neoliberal state. But instead of merely resisting it, Wade described Eastside Projects instrumental complicity within the larger forces of capital and gentrification; “we understand our position as improving the value of the property, and we respect that and use that to get things done.” This instrumentality of the art space, led to a discussion with the rest of the panel as to the instrumentality of the art work. Wade defended art’s right to be “something you didn’t ask for, it necessarily has to have a function of nothing”, a point which Ann Demeester, director of de Appel, contested in terms of the limits of this position in practice. “If we say ‘art is what we want it to be’, the government will simply say ‘well do it yourself.’” De Waal, with one foot in government and one in the private sector, attempted to strike a middle ground by highlighting this conflict between art’s need for subsidies and the desire for independence. Alternatives include the American model, where private philanthropy fills the space of public funds; or for art to enter the political arena, thereby increasing its cultural relevance. Fisher dismissed this model as “literally capitalist realism”, whereby everything including culture is subsumed by the need to justify its economic value. As the general volume amongst the panel members and the audience escalated, it became clear that this issue would not be resolved today. It was clear however, that with new governments and the threats to the cultural sector they bring, art and its institutions need to develop new models that enable them to navigate this changed terrain while protecting the values they have come to stand for.

2.1 Beatriz Colomina

Day two is opened by US-based architectural historian Beatriz Colomina, who presents her research in-progress into the relationship between modern architecture and medicine. The parallels between these two disciplines extend as far back as the Renaissance, particularly through the shared use of the sectional drawing, but, as Colomina argues, it is not until the 20th century with the development of new imaging techniques that architecture and medicine become truly intertwined. “The widespread use of x-rays made new thinking about architecture possible.” Alvar Aalto’s Paimio Sanatorium is likened to a ribcage; Le Corbusier creates roof terraces lifted above the “damp ground, breeding disease”; and most literally, Mies van der Rohe’s stripped back architecture of glass and steel is reduced to “just the skeleton.” Beyond aesthetic metaphors, these same architects saw their buildings as medical equipment, offering measurable health benefits. Le Corbusier’s Radiant City plan is diagnosed as the cure for what he describes as “Tubercular Paris”, and Sigfried Giedion’s publication Liberated Dwellings: Light, Air and Opening chronicles examples of houses as sanatoria. There are fewer contemporary examples to illustrate Colomina’s contention that this relationship between architecture and medicine continues, with the exception of CAT scan imagery used in the monographs of J.L Mateo and UN Studio. More convincingly, is the transfer of medical technology into the field of architectural production, notably Frank Gehry’s use of a laser guidance arm originally designed for brain surgery. Questions from the audience try to relate this generally optimistic trip through history to more concerning trends today including the proliferation of CCTV and full-body scanners used in airport security. Colomina’s response — that just as we allowed the x-ray into our lives with little resistance, these more advanced forms of bodily examination would similarly be assimilated — left little faith in our ability to challenge the relentless march of technology and security.

2.2 Discussion: Hedy d’Acona, Matthijs Bouw and Beatriz Colomina, moderated by Arjen Oosterman

Of the two-day symposium, this session most explicitly examined the conditions and requirements of healthcare design. Dutch sociologist and politician Hedy d’Ancona began with a presentation on the value of design excellence in healthcare buildings, a passion of hers that has led to a new prize named in her honour recognising outstanding architecture in the health sector. The principle is simple — our environments have an important effect on our wellbeing and recovery — but nonetheless one that d’Ancona believes we have lost sight of today. Matthijs Bouw of the firm One Architecture followed with a detailed tour through the complex maze of stakeholders, market demands, architectural heritage, and even religious ideologies of their St Jozef health centre in Deventer, awarded an honourable mention in d’Ancona’s award. Despite these manifold competing demands, Bouw managed to retain some criticality at the end of the process, offering an important counterpoint to the discussion of art’s instrumentality of day one. Even as a commissioned architect working within the market, it is possible to surreptitiously insert activism and a political agenda into a project. The complexity and intelligence of Bouw’s design for St Jozef’s led Oosterman to speculate on why architects have retreated from politics in the past decades. Is it a complicity with the market? Or have we neglected our obligations to society? Colomina detects a renewed interest in criticality and responsibility at the exact moment we face the twin crises of economy and energy. This is ultimately positive, but suggests that architects’ interest in social causes is simply because corporate spending has dried up.

2.3 AA Bronson

Standing on the top step of nOffice’s bleachers, AA Bronson began his presentation with his ‘letter to Amsterdam’. Addressing all those gathered; the students; the queers; descendants of slaves; the immigrants of Surinam and Turkey; the marginalised; the abused; the persecuted; the Jews massacred in WW2; to those who died of HIV aids; Bronson invited them “to join us here to witness this discussion of art, curating and the pairing of this community of the living and the dead.” This equally sensitive and confronting introduction prepared us for a chronological trip through Bronson’s work with the collective General Idea in the 80s and 90s. Mazes of glory holes; self-portraits as babies; Robert Indiana’s ‘LOVE’ image repurposed as ‘AIDS’; AZT pill sculptures; and finally the tragic documentation of Bronson’s partner’s frailty in the final stages of HIV illness, compared to the wasting away of holocaust victims. After five years of “no longer knowing how to be an artist”, Bronson’s art practice and his role as healer converged. Healing sessions held in galleries, all night conversations, and even a range of elixirs, complete what Bronson describes as — quoting Beuys — “social sculpture.” As in the earlier presentation of Chto Delat, the distinction between Bronson’s art and life is blurred. “My healing practice is my art practice * my position as a healer restores me to life. By creating a social context I create a life for myself.”

2.4 Discussion: Nils van Beek, Mari Linnman and Sally Tallant, moderated by Mika Hannula

The final session of the symposium brought together three curators who each presented their own unique models of commissioning artworks and engaging the public in the context of healthcare. Nils van Beek of SKOR offered examples where artists “wanted to make a real difference, not just make a symbolic gesture.” A robotic ape plays tic tac toe with patients in a mental health hospital, representing some resistance to the strict order of the institution. A train carriage is built in a nursing home to give the residents orientation, and an opportunity to withdraw from the relentlessly scheduled program. Van Beek saw these projects and others as contributing to “an ecology of care … a grassroots way of working that can be a real solution to these times.” Mari Linnman, curator of the program New Patrons, described her role as a “mediator” hosting conversations over a number of years with a client group; a process that eventually leads to the commissioning of an artwork. Importantly, these projects are “not always politically correct or socially smooth; when it is correct, it often fails.” “I don’t want art for a few any more than I want education for a few, or freedom for a few.” With this quote from William Morris, Sally Tallant of the Serpentine Gallery established her interest in reaching beyond the artistic community using tools not limited to the exhibition format. This ambition is not merely about involving people, as Tallant made clear, “it’s easy to make a populated practice, but not a participatory practice. Artists plus people does not necessarily lead to sustained engagement.” And sustained it is, like Linnman’s Les Nouveaux Commanditaires (New Patrons), a number of projects under Sally’s guidance have required years of investment in time and community interaction, far beyond the usual level of engagement for an arts institution. Projects relating to ‘care’ included the simple act of introducing Skype into a nursing home, overcoming a draconian ban on internet usage; and the swapping of the artwork in a nursing home with that of the gallery and inviting children to engage with the reality of ageing. The simplicity and power of all the projects presented led to what felt like a moment of realisation regarding the entire symposium. As Andrea Phillips summarised: “art has been getting in the way of the real issue, isn’t the real focus on the quality of the relationships of all the people involved? … To get to that space, I think we have to put art to one side.” While this may sound like a dismissal of the power of art to initiate change, in fact these types of engagements between people could offer seeds for an alternative model for society. “We need to identify ways in which public acting can be exemplary. The forms we are being offered — such as ‘big society’ — are not good enough and we need to publicise the alternatives we are producing.”